Downs Paradox and the Ethics of Voting

A superfluous comment

Anthony Downs, An Economic Theory of Democracy, p.244

Whenever I think about voting, I think about Downs' paradox. Anthony Downs is an early neoliberal economist who set out to describe voting on the assumption that we are rational individuals evaluating a choice between policies and parties and candidates, and that by casting a vote one way or another, we participate in a form of self-government. What Downs argued was that all of this was fine until you noticed that our individual votes don’t matter. In fact, can’t matter. In any group larger than four people, where there is enough of a shared interest to participate in a collective decision as in a vote, the odds of your vote deciding anything are incredibly small. You are either joining or opposing a decision that would already have taken place without you. Downs paradox, also called the Paradox of Voting, is that voting, as an act of rational government, cannot be rationally explained. If you just count the time it takes to fill out a ballot, not counting researching candidates or discussing the issues or walking to the mailbox or driving to the polling station, your effort so greatly outweighs your influence that no rational person would consider it. Even worse, Downs was talking about democracy in the most abstract terms, but in the United States, we vote in a system where the barriers to your vote mattering are much higher. Unless you live in Texas, Florida, Ohio, North Carolina or Georgia, your state is either too small to matter or the race isn’t close enough for your vote to count.

Downs and many of the rational choice voter theorists who came after him have assumed that this means voting has another rationale. This one is less purely egoistic. I am still pursuing my individual self-interest but I recognize that my interest includes a healthy functioning society, so the effort that I undertake to vote is small compared to the potential benefit. And as long as voters are choosing a candidate that will make the country a better place, that fiction continues to make sense. I'm sure you've noticed that we no longer live in that reality. Almost nobody thinks Joe Biden was the right candidate for the moment, and almost nobody thinks Donald Trump is a capable president. For both, their only redeeming quality is not being the other. In this situation, voting has to be doing something else, because even those who continue to do it can no longer pretend that this is about their interest in a functioning society.

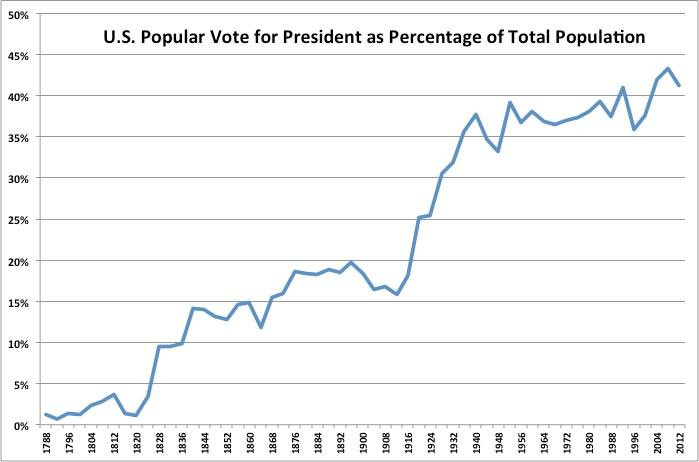

So what does it do? And what has it, perhaps, always been doing? There's the old conspiracy theory that voting is about manufacturing consent. If you have a population who is angry and dispossessed and alienated, you give them a voice and a vote and they’ll let off steam with the illusion of participation. It’s what people implicitly mean when they say, "if you don't vote, you can't complain". Everyone who has heard this and was struck by the answer, "What are you going to do if I complain anyway?" knows that this can't really be the situation. Because most people don't vote. Not once in American history have more than half the people voted for president. Even excluding children, not since 1972 have more than half of adults voted. We have never had the consent of the governed and that has never led to a crisis of legitimacy.

So if it's not rational and it's not a scam, what are people doing when they vote? It's an ethical act. Not in the sense of doing a good deed, but in the sense that by voting people are making a statement about the kind of person they are, the kind of people they are like, the kind of people they are not like, and that this statement is part of becoming that kind of person. It is an ethical act like the choice to be quiet when you see something wrong; by speaking up or sitting down, you define who you have been leading up to that moment and also define your trajectory going forward. If the social scientists are right and our collective preferences have almost no chance of becoming law, and if our votes sway those slim chances none at all, then this is the most significant work that voting does. When you walk away from the ballot box or the mailbox, you have done nothing to sway the result but have done an enormous amount to define your immediate environment, to sour your relationships, to sneer at some, to establish the basis for your interaction with others. Of course, there are always relationships that need souring and people that need sneering at, so it’s not the social cut that matters. It’s that we are stuck having to express these sneers and sours in this artificial environment, pretending that an act of social care is an act of self-government.

This is why an election between Joe Biden and Donald Trump matters so much. In a system where you’re not deciding anything politically, the real effect of your vote is going to be on who you are, and on how you engage with others. This includes the ethical compromises that you are willing to make, the behavior you are willing to pardon, and the people you are willing to ignore and disbelieve. Every few days, we see a new article, announcing that someone doesn’t care if Biden committed sexual assault as long as he’s not Donald Trump, don’t care about his mental lapses or racist comments or his legislative record or his history of opposing abortion rights or his currently stated policies that would kill and immiserate the poor. And the same habit is taking place again in Trump voters, just more quietly because most people who will vote for him already endured this ethical moment years ago. Almost none of these people live in swing states, and yet they speak as if they have made sophisticated calculations, weighing the pros and cons, evaluating the policies. But Downs tells us different. They’re announcing who they are, and what they value, and who they are intending to become.

Dead-eyed cynics are always saying that the ballot box isn’t a confessional, but they underestimate how true that really is. It’s not the confession, it’s the codex. It’s an act that significantly contributes to what good and bad means for the person acting. It becomes part of your moral fiber and your relationship to yourself, to the people in your life. It sets certain benchmarks and help establish the style of your behavior to the degree that you choose to define yourself as the person who voted that way. To vote in these circumstances is not just a waste of time. It is an immoral act, damaging to the soul and to society. My only hope for this disturbing and inhuman choice is that this time, we all find it a little easier to escape.