In order to see the operation of morphological characteristics in myth, I’m going to work through the story of Seolmundae Halmang, or Grandmother Seolmundae.

This is the encyclopedic version of the myth, from the Encyclopedia of Korean Folklore and Traditional Culture Vol. III. It is not more valid than any of the other versions. A myth, after all, is not a story, locatable in single time and place. It is a bundle of all versions, variants and tellings of that story, as well as the effects these versions have on each other, as new tellers try to match fidelity to an original or display their own uniqueness as a teller. The reason I have chosen an encyclopedic account is two-fold. First, it includes some degree of breadth and repetition, including a few alternative paths the story has taken. Second, it is also restricted to only those elements which elaborate and explain the other elements in the narrative, those elements which, if removed, would make the story less intelligible or would disconnect it from the stories around it. This particular encyclopedic version has a third virtue; it is given in two roughly identical versions, the English linked above, and a Korean version. When there is ambiguity or additional information emerging between these two versions, I’ll mark that in brackets as [한.

In our version of the myth, the universe begins with Grandmother's fart:

“In the beginning of the universe, in Tamna [the pre-Korean state on Jeju Island], lived Seolmundae Halmang, the biggest and the strongest being in the whole world. One day, as she was sleeping, the granny sat up and passed gas, which set off the creation of the universe [한:heavens and earth]; islands of flames shook with thunderous sounds and columns [한:a pillar] of fire shot up to the sky. ”

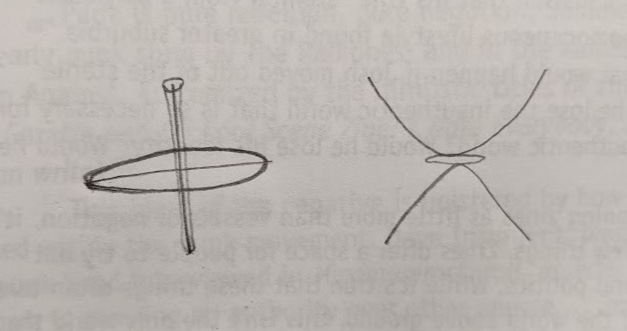

In this version of the narrative, we have two immediate shapes to note; Grandmother's fart splits the whole with a primordial crack, giving us a horizontal line, immediately followed by [a pillar] of fire, our vertical line.

The universe is now divided into two rectilinear oppositions, horizontal space and vertical pillar, crossing each other at Tamna, the land about to emerge into being. However, our contradiction is not a stable one; our straight lines are also curves; a horizon encircles, and a pillar is cylindrical. We see Grandmother Seolmundae set about resolving this dilemma. How to mediate between the line/cylinder and line/horizon? By tracing three new shapes, which either combine the line and the curve, or negate some major element of each. These three shapes are the concavity, the convexity, and the flat "hole".

The granny put out the fire by shoveling up seawater and mud, and built Jeju’s mountains by transporting mud on her skirt, one skirtful of soil forming Mt. Halla and mud dripping from the holes in her skirt forming the island’s many volcanic cones, called oreum.

The skirt, concave, is filled with mud and water, which becomes inverted when laid on the fire pillar, and becomes a mountain, convex. As the for the holes in the skirt, they are 2 dimensional, and look circular from one perspective and like a line form another. Passing through this auto-binarizing shape, we get the mini-mountains, the oreum.

This resolves the seemingly oppositional tension between horizontal & vertical, they are made similar and inversely identical by rotating them 45 degrees, incorporating the circle as curve, while inverting a cylinder (circle with height to circle without height)

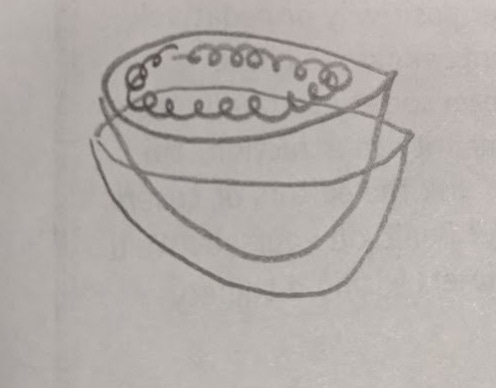

There is a small but very crucial detail about the mountain here. Hallasan, the mountain at the core of Jeju island, is a volcano, so the actual peak is a collapsed crater lake. A concavity at the top of convexity.

This lake is called Baengnokdam, or White Deer Lake. As a short aside, there are two competing myths here; the local one which claims that ancestor gods would climb up and go in to drink wine made from the berries of the white dampalsu tree also known as "White deer tree". The other claims that the gods would go down onto the mountain to hunt on top of Hallasan for white deer which gathered to drink at the lake. (This seems like a later myth because it mimics the mainlander founding myth of Dangun, whose father Hwanung descended from heaven down to Mt Baekdu.)

Let’s turn back to Grandmother Seolmundae, who also made use of Baengrokdam.

The granny was living on Mt. Halla after giving birth to Five-Hundred Generals, but poverty and a bad harvest made it difficult for her to feed such a big family, and she sent out her sons to get food. After all her five hundred sons left in search of food, the granny began making porridge in a gigantic cauldron hung on Baengnokdam, the crater lake on top of Mt. Halla, starting a fire, then walking along the rim of the cauldron to stir the porridge.

Placing a giant cauldron inside the crater doubles the concavity, that remember, sits atop the icon of the island’s convexity, Hallasan. that mounts the c (doubling of the concavity that mounts the convexity) and walking around the rim to stir it (stirring while walking around a circle, tracing a spiral).

Unfortunately, this seems to have be one circle too many.

While stirring, however, Grandmother Seolmundae took a wrong step and fell into the cauldron, drowning herself. The five hundred brothers returned and unaware of what had happened, began to eat, enjoying the porridge, which tasted more delicious than at other times.

We’ll return to the aftermath of this inverted Tantalus, but for now, we need to pause on a few details. This version of the myth is syncretic, merging the story of the 500 Generals with details and forms from two earlier myths about Seolmundae Halmang alone. The first of these myths concerns tainted porridge. In this story, not mentioned in the Encyclopedia version, the oreum were not formed from the holes in Grand-mother Seolmundae’s skirt. Instead, she eats tainted sorghum porridge and has diarrhea, which sprays across the island, and hardens into the 360 oreum hills. Notice how this version of the oreum keeps the three shapes, convex, hole and concave, but the skirt becomes the concavity of the porridge bowl, the hole in the skirt becomes Grandmother's anus (똥구멍, literally shithole), while the convexity of the oreum remains the same.

The second myth takes up the mytheme of Grandmother Seolmundae’s death.

[Granny] was always proud of her immense height: When she stepped inside Yongyeon (Dragon Estuary), known for its depth, the water reached only the top of her foot, and the spring water at Hongnimul reached only her knees. Muljangorimul on Mt. Halla, however, was a bottomless spring and she drowned before she could climb out of the water.

Like with the cauldron, she "puts a foot wrong" and plunges to her death, and also like the Baengrokdam, it is in a concavity at the top of a convexity, this time the lake at the top of the Muljangori Oreum.

However, if we’re focusing on the morphology of the myth, then the similarity is quite strange. In the cauldron version, Grandmother dies from a proliferation of curves, concavity in concavity, and the revolving rotation of the stirred spoon. Here, she falls into an endless concavity, straight now. But what kind of concavity is bottomless? A bottomless lake is not really a concavity at all, but it’s a cylinder, a column, a pillar.

Put differently, the concave goes so deep that it negates its curve, returning to the pillar of fire that Grandmother extinguished with water. Now, it is a pillar of water extinguishes Grandmother, who was herself the primordial source of that fire.

Perhaps it’s time to come back to the 500 generals, having just devoured their mother.

The youngest of the five hundred, who returned last, was scooping up porridge for himself when he found strange bones in the cauldron, and upon a closer look, realized that they were his mother’s. The youngest son lamented, refusing to remain with his disrespectful brothers who had eaten their own mother, and ran off to the faraway island of Chagwi off the village of Gosan in Hangyeong-myeon, where he wept and wept until he turned into a rock. [한:The brothers who saw this finally knew the truth and stood here and there, wailing endlessly, and all of them were hardened into rocks.] Thus today in the valley of Yeongsil can be found the four-hundred-and ninety-nine generals and the youngest brother, on his own, on Chagwi Island.

With the Muljangori Oreum pool, we have the conjunction of the flat circle and the infinite column, as the placid depthlessness of the pond’s surface becomes the infinite drowning chasm below. In both instances, the morphology is singular; one absolute circle, one absolute line. With the cauldron myth, we have many of the same transitions but not singular to singular but multiple to multiple. Rearranged, the myths show Grandmother falling in the singular liquid porridge, reduced to her multiple bones, recognized first by her singular son, who passes, along with his many brothers, through the many liquid tears to become hard stones. We can now return the diarrhea myth to the transformation set, as it was grandmother’s single bowl of porridge which scattered many liquid feces across the island, which harden into many stones.

So what does this mean and what does it not mean? This kind of myth reading has a very bad reputations, so we should begin with the latter. It doesn't mean that the meaning of the myth is this morphology. Nor does it mean that by reading the myth this way you can partake in the shared mind of humanity recognizing itself. You can't, without being a colonizing prick, overwrite the myth with an interpretation. What is done in the act of interpreting is, instead, another instance of the myth. Just as Freud was in the strain of Oedipus, so too was Levi-Strauss’ discussion of Freud and Sophocles and Oedipus in The Structural Study of Myth.

Here, giving an interpretation takes the general principle, taken more loosely by some than others, that all retelling is interpretive. The ethical burden is then to make an attempt for this interpretation to be legible and meaningful to the spaces where the myth now maneuvers. The attempt can be parasitic, swallowing up exotic authenticity to concentrate power in the interpretation, or it can contribute, by lending itself to the form which it interprets.

As a structural relation, intention doesn't matter. Freud wasn't trying to re-invigorate Oedipus Tyrannus for another hundred years, but he did, calling in new interpreters and enlivenings. Meanwhile, many mid century anthropological universalists ended up devouring the cultural objects they were trying to preserve and care for, precisely when they arrived with a eurocentric humanist antiracism.

On the other hand, there is such a thing as being too precious with myths, imposing fantasies of lived authenticity where they don't exist, fearing contaminating some secret pure religious expression from there with dirty critical analysis from here. Seolmundae Halmang, for instance, was not a live myth. It has not been part of the traditional Jeju shamanic religion. Instead, it's an easy-bake origin myth, with few complexities, good enough to sell a tourist brochure, but but too general for an island which has many significant regional divides. However, having been brought into the island-wide identity, as that has increasingly become the mode of Jeju sociality in the last 20 years, Seolmundae Halmang has reportedly emerged within some shamanic ritual re-tellings. By circulating an image, the Tourist industry concatenated an egregore, which then opened itself up to engaged use and shamanic "presence-offering".

So why does this morphological reading matter? Because as long as we talk about myths as stories that live most authentically in localities, as actually operating narratives which play complex role in partitioning gender, clan, land, elements, geometry, not metaphorically but ontologically, then we’re not talking about myths. Those are creation stories, and those sit outside the bounds of critical interpretation, not because of some dogmatic privilege, but because once they depart from the world of their ritual reality, the conditions of their objecthood collapse and they become something else. That something else they become is a myth, where elements are reduced to an enmeshed narrative, stripped of their immediate actualization and distributed, to where no reader or listener can be engaged in them.

What is at stake in this shift? If we say that the telling of a myth requires, in order not to be parasitic, to return to the space of the transformation set with a new elaboration of the possibilities of interpretation, then that space is not the space of Jeju, or the space of some fantasized island resident who thinks of a nearby hill as dried shit. The question of Levi-Strauss' structuralism was one of reflection; if humanity is to be intelligible to itself, it must be because there are structures in common in both the mind and world which can reconcile. And so too, human beings. It’s a major thrust of this kind of work to establish that indigenous people, and particularly nonliterate peoples, are as fully human as those who claim to analyze them. For this argument, we all participate in a wild and roving rationality, with our world-embedded minds refecting on a mind-imbued world.

The purpose of splitting the myth from the creative act is to establish the question as one of communication. The “law-like properties” of the relation of minds to the world is not the result of a shared structure between those two fields, some reconciliatory potential of either embodied materialism or speculative idealism. It is instead the effect of objects which have been processed in a particular way, that is, communicated.

By noting the regularities in the myths, we trace the structure of communicated things in exactly the same way Levi-Strauss thought he was tracing humanity's roaming actualized rationality. On this mark, I’m totally Nietzschean, not just in the aphoristic sense that metaphysical problems are grammatical habits, as if we just need to shake off the tongue-tie of non-contradiction and objecthood, but in the sense that what is called mind is the communication system.

Where Nietzsche, and Levi-Strauss too, fall behind their own thinking is their reliance on the word. If consciousness is communication, neither the Thinking nor the Being-that-is-thought, we’re not limited to a question of grammatical regularities at all. In fact, for all the excesses of the linguistic turn, it wasn’t enough to extend regularities that lacked conceptual divide, regularities of images, of smells, of touches &heats.

Noam Chomsky once famously said to Andrew Marr, “I’m sure you believe everything you’re saying. But what I’m saying is that if you believe something different, you wouldn’t be sitting where you’re sitting.” To say that the narratives of the Seolmundae Halmang myth start to fit inside themselves is true, and it is neither the projected fantasy of an overtheorizing academic nor the reality of the story as once told. It is, instead, the effect of the circulatory motion of communication itself which latched onto this well-fitted specimen.

The virtue, and power, of morphological discourse analysis, whether of myths or any other well-delineated media, is that it can begin to take seriously the shape of communicability itself. The question isn’t why this myth has these interlocking elements, but why it has these interlocutionary elements. What communicability features were incipient in the oral practice? What made it amenable to move from a locality, and orality, a creation story, to be recorded in this encyclopaedical style? What labor apparatuses and techniques were available to drag it across these conceptual lines, and how had those been established in the first place?

It is immoral for an essay to end on a litany of unanswered questions. Not only that, but Grandmother Seolmundae deserves a proper interpretation. The narrative returns again and again to twists and torsions, to the passage of one form to another through a strange mediator; tears, a [shit]hole, a burning pillar of fire thrust through the crack of l'origine du monde. But the engine of the story, what makes it communicable, is its clear and comfortable strangeness. The story is isolated because it is an origin myth, not of the people but of the island. Tourist brochures and cultural organs need origin myths because they need to fill social calendars with people-gathering events.

But it doesn’t motor on because it’s completely coherent, as if you just had to swap the pieces around to see how the skirt and the hole and the anus and the mountain are all dominos to be matched. It moters, on the contrary, because it’s complete insane. Grandmother is in Tamna, the island nation that ruled Jeju before Korean colonization, before even the split of heaven and earth? Without land to rest, where did she sleep? I can deal with a fart tearing the world in two and piss blasting off corners of the island, but how do you cry yourself to stone? I didn’t even mention the frankly obscene story of Grandmother Seolmundae’s vagina, which is as large as the Whale’s Cave and is constantly being exposed because she’s too large for completed clothes. When she asks the islands for some, they get her 99 barrels of silk, just one short of her request for 100, to make a full vagina-covering dress, so she makes it with 99 and my goodness, she’s somehow managed not to leave out a patch over the knee or to hike the hemline, no, it’s her vagina that remains exposed.

Grandmother Seolmundae’s body was rich and fertile, carrying everything inside: The people of Tamna plowed fields on her soft flesh; her hair turned into grass and trees; the powerful streaks of her urine gave birth to all types of seaweed and fish, octopus, abalone, and sea conch, enriching the sea and making the way for the profession of Jeju’s women divers.

If I were a structuralist, I would claim this story is fundamentally about the reconcilitaory and reflective logics of line and curve, akin to some Jeju Pythagoras or Liu Hui, allusively describing the geometric mysteries. But that’s easy. Anybody with a stick and dirt has invented the line and the curve. Grandmother Seolmundae is in this story, and is communicable, because she’s weird. The story is about the incongruous impossibility of a Grandmother digging up an island of her own body, carrying the whole inside, being plowed upon and therefore being the land that she also stands on to wash her ragged clothes, dirtied by her own mud, drowned dead in an infinite pool in the middle of her own dried diarrhea.

To hear the story of Grandmother Seolmundae is to be shocked. If you’re anything like me, what you want now is another source. This can’t be right, the encyclopedia has it wrong or it mashed up too much or it’s gotten all garbled through the years of transmission. Transmission is transmutation. And not because the letter gets folded, but because the transmutation is what is transmitted. Now that you want another source, you find one, and you start to build your own little collection. You too notice that this one doesn’t have the diarrhea stuff, this one over here suggests that the peurile stuff about shitholes and farts is later additions, and that the original is a simple creation of a world split and a mother making room for her children. At that point, you’ll have a transformation set of your own, and a rough working theory of how the narrative circulated, and the transmutation will be set to work all over again.